‘I can’t relate to it any more:’ How Destanee Aiava found joy after hitting rock bottom

But Aiava’s had much bigger victories away from the court than her three-set win this week from double match point down over Belgian Greet Minnen. She bravely revealed in 2022 that she planned to take her own life, only for three strangers to intervene. That terrible moment in Aiava’s life has been in high rotation in the coverage of her on-court exploits at Melbourne Park, but she does not recognise that person. “I see a lot of articles about it, and it just makes me laugh because it’s not who I am any more,” Aiava said. “I can’t relate to it any more, and it feels like a completely different person. I don’t even know why it’s a thing any more – well, I do, and it’s really good to speak about, which is why I told people at the time. But I just can’t see myself in that position again, or right now, which is good. “It was a really low time in my life, and it did teach me a lot, and I had to reach rock bottom to be where I am now. [But] I wouldn’t recommend anyone going to rock bottom.”

Aiava with her fiance Corey Gaal. Credit: Simon Schluter Later that same year, Aiava was experiencing panic attacks daily before matches at a tournament in Darwin, which she made the final at. She told Corey she needed to speak to someone to finally find out what was happening to her, which led to her diagnosis of having borderline personality disorder (BPD). BPD impacts how people manage emotions, how they relate to others, and can result in instability in relationships, mood swings and impulsive behaviour. “It was a relief, but then it also felt like a death sentence because it’s something that I have to live with my whole life,” Aiava said.

“There’s no cure for it. You just need to make sure you’re in a really good environment and always self-aware about bad things happening and making sure things are OK, and it’s not as bad as it seems, even though it does feel like the end of the world all the time.” BPD is not something people are born with. “It’s mainly from childhood trauma, so things in your brain develop poorly as a child,” Aiava said. “Being in a relationship makes it [BPD] worse and just like fear of abandonment and all that stuff. Corey being able to grow with me through all of that stuff has been a massive help. Aiava represented Australia at Roland-Garros when she was just 12. Credit: Paul Rovere

“ I feel like in a Polynesian culture, mental health isn’t talked about enough, and it’s kind of looked down upon, which I know a lot of Polynesians deal with, and they struggle with, so I was just a product of that as well. “But [family] have definitely gotten so much better at learning about mental health and also dealing with me as a child and everything I’ve gone through. They’ve been really supportive.” Aiava’s parents, Rosie and Mark, are no longer together, but she speaks to her mum “every single day”. Mark lives on the other side of Melbourne now, so does not see Aiava as often, but they remain in contact. “I try not to look back on [my childhood] too much,” she said. “I just try to remember the good times and all the hard work that I put in that has led me up to this point. But when I do think about it, I try and look at all the positives.”

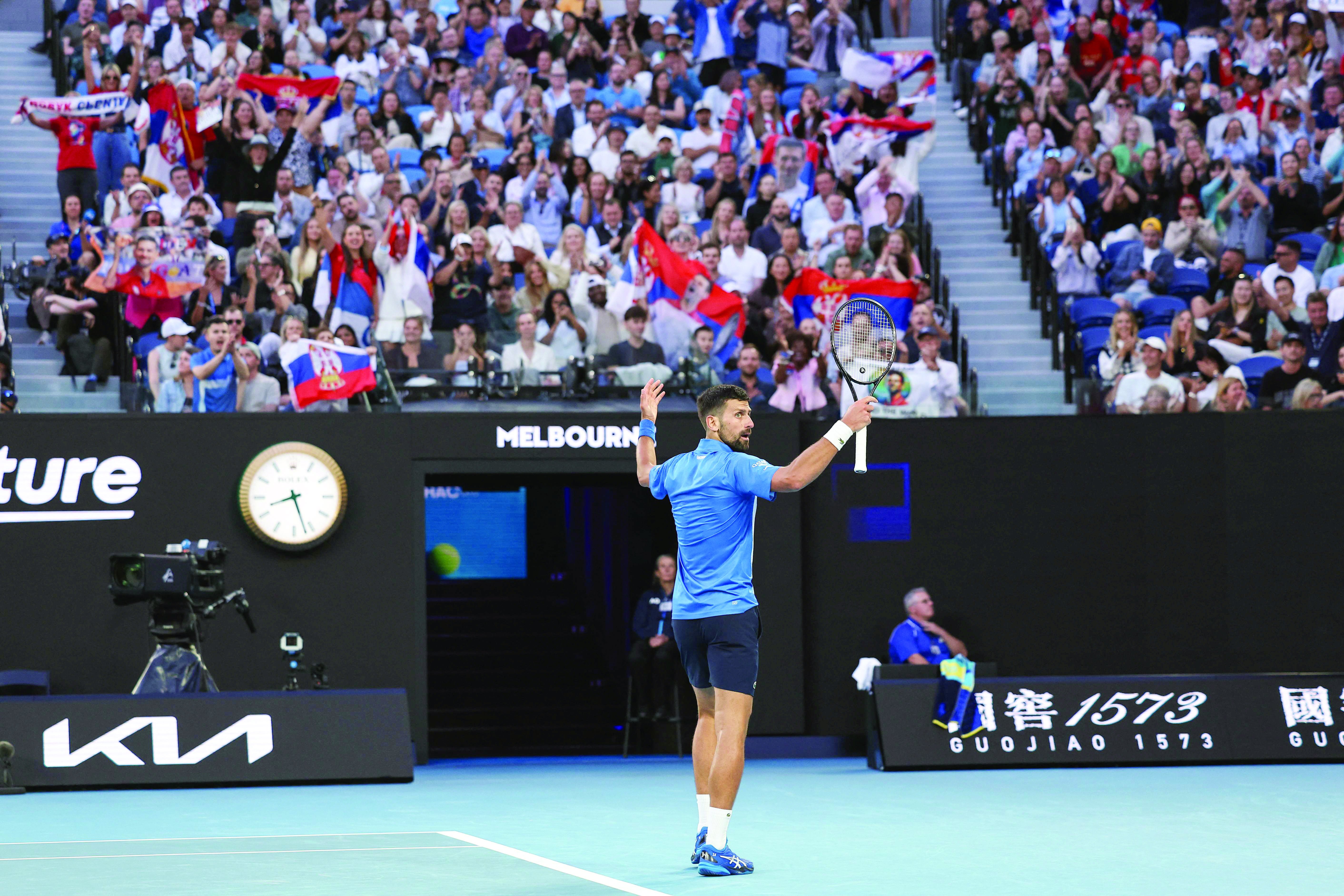

Loading Aiava likes being open about her journey, and hopes by doing so that she can help others, an initiative she might do more of in the future after her tennis career ends. But before then, Aiava is intent on realising her potential with a racquet in hand. There is genuine momentum again, after qualifying at last year’s US Open and now winning a round at her home grand slam. “I think as bad as comparison is, I think that’s something that has helped me – just seeing everyone else do what I want to do, and being tired of being mediocre, and feeling like an underachiever,” she said. “It has been something that has pushed me to want to do better. I mean, there are so many young girls doing what I want to do, and then watching the Olympics as well [was a trigger].

Aiava with her fiance Corey Gaal. Credit: Simon Schluter Later that same year, Aiava was experiencing panic attacks daily before matches at a tournament in Darwin, which she made the final at. She told Corey she needed to speak to someone to finally find out what was happening to her, which led to her diagnosis of having borderline personality disorder (BPD). BPD impacts how people manage emotions, how they relate to others, and can result in instability in relationships, mood swings and impulsive behaviour. “It was a relief, but then it also felt like a death sentence because it’s something that I have to live with my whole life,” Aiava said.

“There’s no cure for it. You just need to make sure you’re in a really good environment and always self-aware about bad things happening and making sure things are OK, and it’s not as bad as it seems, even though it does feel like the end of the world all the time.” BPD is not something people are born with. “It’s mainly from childhood trauma, so things in your brain develop poorly as a child,” Aiava said. “Being in a relationship makes it [BPD] worse and just like fear of abandonment and all that stuff. Corey being able to grow with me through all of that stuff has been a massive help. Aiava represented Australia at Roland-Garros when she was just 12. Credit: Paul Rovere

“ I feel like in a Polynesian culture, mental health isn’t talked about enough, and it’s kind of looked down upon, which I know a lot of Polynesians deal with, and they struggle with, so I was just a product of that as well. “But [family] have definitely gotten so much better at learning about mental health and also dealing with me as a child and everything I’ve gone through. They’ve been really supportive.” Aiava’s parents, Rosie and Mark, are no longer together, but she speaks to her mum “every single day”. Mark lives on the other side of Melbourne now, so does not see Aiava as often, but they remain in contact. “I try not to look back on [my childhood] too much,” she said. “I just try to remember the good times and all the hard work that I put in that has led me up to this point. But when I do think about it, I try and look at all the positives.”

Loading Aiava likes being open about her journey, and hopes by doing so that she can help others, an initiative she might do more of in the future after her tennis career ends. But before then, Aiava is intent on realising her potential with a racquet in hand. There is genuine momentum again, after qualifying at last year’s US Open and now winning a round at her home grand slam. “I think as bad as comparison is, I think that’s something that has helped me – just seeing everyone else do what I want to do, and being tired of being mediocre, and feeling like an underachiever,” she said. “It has been something that has pushed me to want to do better. I mean, there are so many young girls doing what I want to do, and then watching the Olympics as well [was a trigger].